Testimonies of Isa, Silvia, Melitza, Rossana, Clemencia, Pilar, and Diana, seven women who were kidnapped by the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional) from the Church of La María, Cali, Colombia, on May 30, 1999.

Rossana: We went to Mass every Sunday, my husband and I, at ten o’clock in the morning... To the La Maria Church. We were even a little late. We sat where we always sat. During the moment of Elevation, we began to see trucks arriving with people dressed in military clothing, and we were convinced they were military personnel and maybe they were going to search the church. They surrounded the church and one of the guerrillas went behind the priest and whispered something to him. Then we heard the priest say, “The gentleman has just told me there is a bomb. Please evacuate the church.”

Isa: In the beginning, the first ten days were about getting to know each other, right? And how to give everybody private space. We all tried to do this. But once meeting each other is over, once we think we know each other, each person begins to act like they really are. So we begin to have disputes over personal space. Eleven of us slept on the ground in a space not more than five yards long. You realize it’s impossible to sleep, even in a fetal position, that the only position to sleep in is stretched out. It is vital to change your position in the middle of the night, just a little bit. So then you see that your neighbor doesn’t want to move, and that the neighbor took five centimeters of the bed—if you can call the ground the bed. That war made coexistence very difficult. The moment came when those differences became an unsustainable situation.

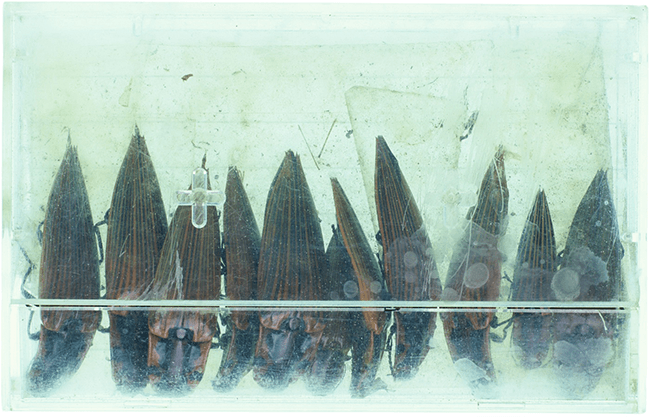

Caja de cassette / Cassette box

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Rossana: We began with the first insect and we got a box where we started collecting the insects, using the techniques I had learned in entomology but with whatever we had at hand. A cassette tape box, some felt cloth, and a needle we happened to have. I would try to spread the insect’s legs and wings with the needle. Then I showed Melitza how to do it.

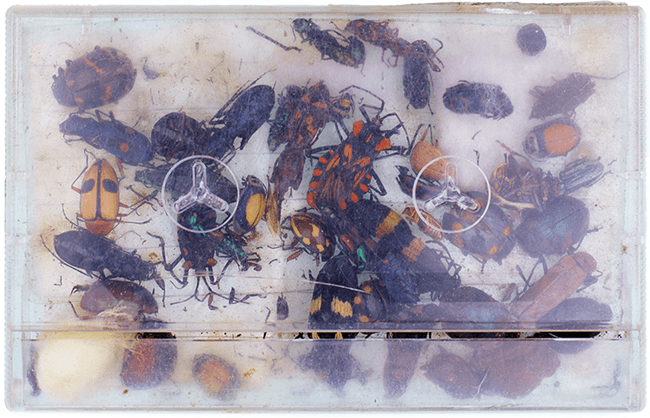

Estuche / Case

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Isa: In the area of the Pacific where we were, the colors of the insects was most marvelous. There were insects that we called “the little seeds.” They were like cockroaches, but elongated, and they could bend and jump. “The little seeds” were red, yellow, and black. There were some that would lift up their little wings and fly. They looked like iridescent helicopters with the most precious coloring.

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

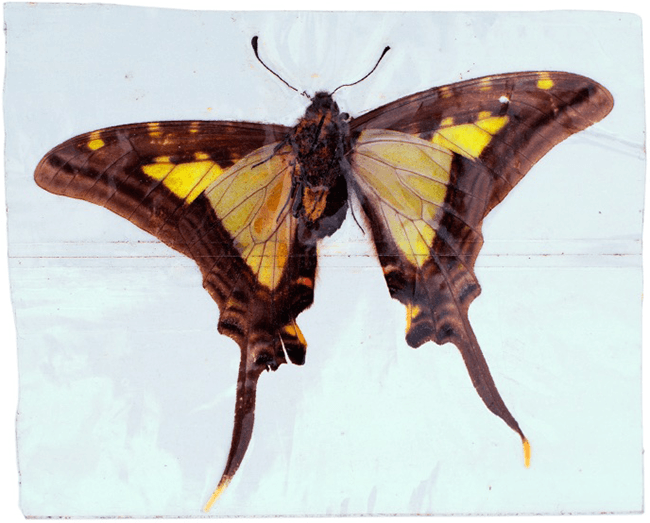

Isa: We were high up in the mountains. It was very cold and I heard one of my brothers on the radio. He began to talk to me, very poetically, about butterflies. I was barefoot... and a yellow butterfly with red fringes landed on my foot. Later when we carved the rocks, I carved a butterfly on a rock for my brother.

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Rossana: Lots of things happened with Mother Nature. I remember that the biggest support for me was finding drinking water. At every waterfall I came upon, at every river, I would drink water, always.. and I would say, “Look; Beloved Father. If you put this water here, you did it for a reason. I’m going to drink it. You’re going to give me strength. I don’t know how far away the next drink is.” Really! There were times we would go for four hours without finding water. But at the waterfalls it was... religious to stop. To us, it was religious to look at the water, splash ourselves, drink, and then continue on.

Piedras / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Olla / Eating bowl

2000

76x102 cm / 30x40 in

Fujiflex print

Estuche / Case

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Cajas de cassette / Cassette boxes

2000

102x76 cm / 40x30 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

50x40 cm / 20x16 in

Fujiflex print

Mariposas / Butterfly

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Piedra / Stone

2000

25x20 cm / 10x8 in

Fujiflex print

Olla / Eating bowl

2000

76x102 cm / 30x40 in

Fujiflex print

Testimonies

Isa: It was a very dark night because the moon had abandoned us. We walked and walked and we climbed and climbed. I remember that Oscar Julián was walking ahead of me and all I could see was something white inside a bag he was carrying. The shine guided me.

Silvia: It was very difficult for the women who were wearing shorts because they felt the cold from the start. It was a rocky path where you could hurt your feet and toes, and those in shorts even more so because they were wearing sandals, with no protection for their feet. A lot of us lost our toenails.

Rossana: Monday, June 28. Thirty days. We have been listening to the radio and we still know nothing of our letters home. It has been raining since the day began. We don’t want to move from our tent, which makes our stay even more depressing. Hives are beginning to appear on our hands. It looks like carranchil (a tropical skin infection). At night they itch a lot. During the afternoon we heard that our companions sent letters as proof of life. We are happy to have word of them. Apparently they are in a cold area.

Silvia: The men cried, as well as the women. Many of them would look for a place to cry, to totally relieve themselves. At other times we would all cry. When the radio program was on, we would cry when we heard the messages, even if they weren’t for us. But the messages touched all of us, and that is when we would feel everyone’s pain.

Clemencia: Sometimes we would ask the guerrillas if we could help them in the kitchen, help them prepare the food. The few times when they brought vegetables, they didn’t know what to do with them. So we showed them how to wash the vegetables, keep them fresh, and how to cook them.

Silvia: The day of the kidnapping, I was dressed like I seldom dressed. I was wearing long pants, a T-shirt, normal shoes and socks . . . and I never dress like that. I always wear skirts and sandals. But that morning I opened my closet and took out those clothes without knowing that those were the right types for where I was going.

Rossana: We went to Mass every Sunday, my husband and I, at ten o’clock in the morning . . . to the La María Church. We were even a little late. We sat where we always sat. During the moment of Elevation, we began to see trucks arriving with people dressed in military clothing, and we were convinced they were military personnel and maybe they were going to search the church. They surrounded the church and one of the guerrillas went behind the priest and whispered something to him. Then we heard the priest say, “The gentleman has just told me there is a bomb. Please evacuate the church.”

Melitza: They loaded us into the trucks. It was very upsetting because they wanted it to happen in a matter of seconds but there were too many of us. We are almost 150 people in the church. There were children, elderly people, obese people. It was a very tormented moment, because we were afraid and we didn’t know what to do.

Silvia: I was held captive for 165 days. The longest 165 days of my life, and the saddest.

Clemencia: Usually we would reach places where there was so much mud it would almost reach our waists. To arrive at night, after walking through all that mud—even our boots would get uncomfortably full of mud. To not have a way to bathe, or any way to clean the mud off was so hard, so difficult, that sometimes I would cry. I would get terribly depressed. As time went by, I decided that if I didn’t show myself some love, if I continued to sink into those depressions, it would all come to nothing in the end. So I decided to believe that everything I was going through, including the mud, was part of Nature. I decided that the mud, which I hated so much, was part of my life. I learned to love and appreciate it until there came a moment when I didn’t mind the mud. I coexisted with it and with the discomforts of the climate and everything else. I began to adapt to the point that I loved everything around me—but it took me three months to reach that mental state.

Isa: In the area of the Pacific where we were, the color of the insects was most marvelous. There were insects that we called “the little seeds.” They were like cockroaches, but elongated, and they could bend and jump. “The little seeds” were red, yellow, and black. There were some that would lift up their little wings and fly. They looked like iridescent helicopters with the most precious coloring.

Melitza: When the sun came up, I would begin to see swarms of insects with beautiful colors and forms.

Isa: There were ladybugs of all colors, yellow and blue ladybugs, red ladybugs.

Melitza: I began to think about my boy, Esteban, who loves insects and lizards. He likes to pick them up so I thought that insects would be a nice gift for him.

Rossana: You’re always thinking that you want to take the seed, the stick, something back as a gift. We began with the first insect and we got a box where we started collecting the insects, using the techniques I had learned in entomology but with whatever we had at hand. A cassette tape box, some felt cloth, and a needle we just happened to have. I would try to spread the insect’s legs and wings with the needle. Then I showed Melitza how to do it.

Melitza: I started to put together an insect collection. We began to see that, as I put together this collection, the guards began to enter a world that, although surrounded by it, they had never noticed before.

Rossana: So every afternoon there was an official visit by almost all the guerrillas to our tent to see our insect-filled boxes. I would say to them, “Look at the beauties in here. This is Colombia.” Melitza: We tried to decorate our tent with flowers, beautiful flowers with marvelous colors. So the guards started bringing us flowers as well. Every day one of them would bring a new flower for our tent. Diana: The silence in the jungle was sometimes very beautiful because we could hear the sounds of nature: the birds, the wind, the rustling of the leaves in the trees. We would concentrate on all the sounds, but there were other scary moments when we couldn’t hear anything. It was like being in a hole, like the living dead. Rossana: We had a lot of free time. It is one of the things that saddens you during a kidnapping . . . and at the same time, causes you to ask yourself, “Now that I have all the free time that I wanted so much when I was in the city, what to do with it?” So you start to delve into many personal reflections.

Isa: In the beginning, the first ten days were about getting to know each other, right? And how to give everybody private space. We all tried to do this. But once meeting each other is over, once we think we know each other, each person begins to act like they really are. So we begin to have disputes over personal space. Eleven of us slept on the ground in a space not more than five yards long. You realize it’s impossible to sleep, even in a fetal position, that the only position to sleep in is stretched out. It is vital to change your position in the middle of the night, just a little bit. So then you see that your neighbor doesn’t want to move, and that the neighbor took five centimeters of the bed—if you can call the ground the bed. That war made coexistence very difficult. The moment came when those differences became an unsustainable situation. So we divided ourselves into two groups. We were Us and Them. We began to have arguments or we didn’t talk to each other. The situation was getting insufferable. And we all started to feel, simultaneously, the need to talk with the others. And finally the moment came when someone dared to wash out his or her wound, to say “I didn’t like what happened. It hurt me to hear you say this or that.” It was marvelous to see how we all began to transform our attitude towards each other. It was possible to give up terrain. It was possible to recognize your own mistakes. We achieved a coexistence where we understood what being tolerant with each other meant, where we understood the importance of accepting others as different from oneself. When you understand that, it’s much easier to coexist. And the most marvelous thing about this story is that after the five months, we came down [out of the mountains] as eleven siblings.

Clemencia: We developed a ritual to say goodbye to our companions when they were going to be freed. It was a very intense moment for us. We would hug in a tight circle. We wanted to be as close as possible to each other. We would say a prayer and a few words to express our feelings for this person who was going to leave. Our way to say goodbye, to seal the moment with something “ours” alone, was to roar like a lion.

Isa: We would put all our effort into it, everything—everything we had inside—and in a very loud shout we would tell the person who was leaving goodbye. At that moment, the person was still with us but we could see how they would walk away with their pack and three or four guerrillas to accompany him or her. So three or four times, those of us who stayed behind would do the roar very, very loud so that the person leaving would take our voices with them.

Diana: He became a very good friend of mine, practically a courtesan. He was the assistant to a bus driver. He had a brother who was a member of the FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] so he decided to join the ELN [National Army of Liberation]. He was always trying to get my attention, to get affection, to feel loved. But they can’t have those luxuries. They aren’t friends among themselves, only companions. And they say that companions are loyal to the organization, yet not loyal to friends. A companion defends his organization. He would say to me, “The only friend I have here is Pablo, and I don’t trust any of the rest; nobody, nobody, nobody.” So the five months and one week that I was there, he was always with me. And when I left that place, well, we cried and that was the end of our friendship.

Clemencia: One night, we were about to go to sleep, when one of the guerrillas who talked to us the most told us about our guerrilla companion. This person from the start showed a lot of interest in us. He often accompanied us. He cooked our food with love. He, even though he loved us, was tired and wanted to leave the guerrilla militia. Well, on my birthday, since he knew that I loved to eat arepas (corn patties) and beans, he asked to make my lunch. And he made it spectacular, with a lot of love, for which I thanked him. After that, they took him out of there. One night they told us that the guerrilla militia had executed him because of his misbehavior. That news was a very hard blow.

Isa: We were high up in the mountains. It was very cold and I heard one of my brothers on the radio. He began to talk to me, very poetically, about butterflies. I was barefoot . . . and a yellow butterfly with red fringes landed on my foot. Later when we carved the rocks, I carved a butterfly on a rock for my brother.

Silvia: For me, nightfall was the worst moment during the day because the cold was terrifying. We would sleep tightly together to give each other warmth but sometimes it wasn’t enough. . . so almost all of the nights were spent awake.

Pilar: Walking in the dark. I actually thought that if I fell off a cliff, it would be the solution. One of my companions, right at the moment that I was desperate, gave me his hand. It was like life yanked me along, saying, “Let’s go!” I remember all that day; he held my hand until we reached the place where we were to sleep.

Silvia: The walks were so long, one right after another. After two-and-a-half months, my knees started to bother me. The moment came when the pain and swelling was so much that the knee would get rigid and impossible to bend. One of the guerrillas had to carry me on his shoulders. I could no longer fend for myself.

Clemencia: We saw water of all colors. We saw red waters, golden waters, gray waters, blue, green. And it’s not that the water was colored, the rocks in the rivers were those colors.

Rossana: Lots of things happened with Mother Nature. I remember that the biggest support for me was finding drinking water. At every waterfall I came upon, at every river, I would drink water, always . . . and I would say, “Look; Beloved Father. If you put this water here, you did it for a reason. I’m going to drink it. You’re going to give me strength. I don’t know how far away the next drink is.” Really! There were times we would go for four hours without finding water. But at the waterfalls it was . . . religious to stop. To us, it was religious to look at the water, splash ourselves, drink, and then continue on.

Silvia: The work we did as a group, the most important work we did . . . were the rocks that we took out of the rivers and learned to carve.

Melitza: It all made so much sense. It was bringing a gift back to your friends. It was finding a moment in time to meditate, to hope.

Silvia: I was able to collect about 30 stones, which I gave out among my family. In the last few days we also brought very beautiful flowers. And we brought the affection of all our companions.

Pilar: The starry nights were so beautiful. There were thousands, thousands, millions of stars. And at night when you couldn’t sleep, when you would stay up looking at the night sky, you sometimes could see millions of falling stars.

Rossana: We had another beautiful relationship with the birds. I remember that I spoke to them a lot. The day before my liberation, a great number of birds showed up in front of our tent. I had been sick that week with a cold. I hadn’t been feeling well and all week long many birds with spectacular colors had come. That afternoon in particular, they made a lot of noise in front of the campsite. So we began to talk to them. I told my companions, “Look, they have a message for us. They’re bringing something for us. What are they going to tell us?” And I would ask them, “What do you want to tell us? That our families are okay? Okay! That we’ll be leaving? Okay.”

The next day, Saturday at ten in the morning, one of the guerrillas said to me “prepare your pack because we’re leaving.” This farewell was very painful, very painful. During the entire walk all the way to a big river—around three or four hours— three little yellow birds that had been up at the campsite the whole time accompanied me. They were beside me, and I was walking very fast, coming down, and the whole time they were criss-crossing my path. So I said to them, “That’s what you were telling me, and now you’re going to come with me. How far are you going to come with me?” I spoke to them all the time and the guerrillas would look at me like, “this lady went crazy.”

Pilar: When we began to walk, there was a bird that followed us from camp to camp. We would say that the Holy Spirit was traveling with us. It was a black bird with an orange beak and, unbelievably, that bird would arrive at our campsite, campsite after campsite . . . after ten or twelve hours of walking. He never left us until we reached the last campsite before liberation.

Isa: Normally we would walk through the middle of the river, coping with the rocks. The rocks were slippery, and you felt like you were going to slip . . .

Isa: But we learned how to walk there. And that day we walked through the middle of the water. The river kept getting deeper; the water was almost up to our waists. We began to climb upriver. We came to a stream that flowed into the river when it began to rain torrentially.

Isa: There was a lot of mud, and we were moving along with the hope of meeting up with our companions. It was as if we were walking to freedom and we would walk and walk and even though there was mud and rain and cold, we were headed to an encounter, and that gave us strength and energy to continue walking. Suddenly we arrived at the middle of nowhere, on the banks of a beautiful river with golden rocks . . . to simply arrive at the banks of a river. It was the wilderness, the plants, the water.

Clemencia: And I started crying and crying and crying. I would tell them “I want to die.”

Isa: We were in the middle of that trauma when a guerrilla woman appeared out of the wilderness, a beautiful woman! She was a black woman, about fifteen years old. And she had very white teeth. Our immediate reaction was to give our special greeting, like the roar of a lion, initially a yawn but gradually acquiring volume and finally becoming our secret code. So then Luis does the roar of the lion and when we hear, far off in the wilderness, the answer from our companions who were coming down, doing their lion’s roar . . . that was . . . that was really . . .

Pilar: The day that Omar left the camp was the day our lion’s roar had so much strength. He was the first one to be freed and from that day on it brought us together more each day, more and more becoming our cry of freedom.

Rossana: Thursday, August 12th. Seventy-five days. I woke up feeling better. Thank God. I prayed to the Virgin last night for my health. Among all of us, we began to compile the Manual for Kidnapped People. We’ve laughed a lot. There were lines about all the things you should always have with you, since the situation in this country is such that you don’t know when you’re going to be taken. We began with all the things that we didn’t have during our time on the jungle mountain: toothbrush, panties or underwear if you’re a man. You should have written music, which is vital. You should have toothpaste. You should have the book you’ve never read but that you want to read. Hopefully, you should carry an inflatable pillow. We missed having pillows.

Rossana: I remember one of our companions who made us laugh and laugh. We couldn’t take it anymore. She would say, “Look, every month, you and your family and all your neighbors get into bed together, in the main bedroom, and notice how everyone starts to turn over in bed in the middle of the night, first to the left and then to the right. Coordinate yourselves and you have begun your preparation for being kidnapped. Once a month, climb into the refrigerator. Feel how the cold reaches your bones. Once a month, make some mud. Imagine you have pigs in your house and get into it, get muddy, cover yourself with mud until you feel like the most horrible thing in the world. That’s part of the preparation that must be done for being kidnapped. About meals, do the same thing. Once a month prepare a disgusting meal. Put spaghetti and lentil beans in the same bowl and add all the grease you want and eat it, deliciously. Imagine you are having a great feast. That’s how you prepare yourself for captivity.” That was part of what we had to live through, what we cried over. When we experienced those moments we cried intensely and when we finished crying, we wrote about it.

Installation view

Centro Cultural Palatino, Pasto, Nariño, Colombia, 2019